Seaweeds Of New Zealand

A Seaweed is a particularly wholesome food, which absorbs and concentrates traces of a wide variety of minerals necessary to the body’s health. Many elements may occur in seaweed – aluminium, barium, calcium, chlorine, copper, iodine and iron, to name but a few – traces normally produced by erosion and carried to the seaweed beds by river and sea currents. Seaweeds are also rich in vitamins; indeed, Inuits obtain a high proportion of their bodily requirements of vitamin C from the seaweeds they eat. The health benefits of seaweed have long been recognised. For instance, there is a remarkably low incidence of goitre among the Japanese, and also among New Zealand’s indigenous Maori people, who have always eaten seaweeds, and this may well be attributed to the high iodine content of this food. Research into historical Maori eating customs shows that jellies were made using seaweeds, nuts, fuchsia and tutu berries, cape gooseberries, and many other fruits both native to New Zealand and sown there from seeds brought by settlers and explorers. As with any plant life, some seaweeds are more palatable than others, but in a survival situation, most seaweeds could be chewed to provide a certain sustenance.

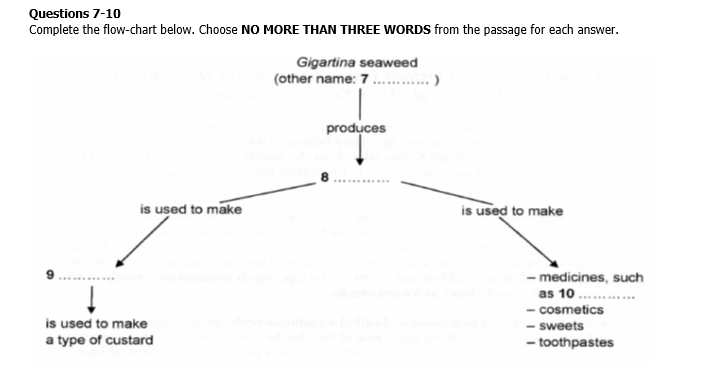

B New Zealand lays claim to approximately 700 species of seaweed, some of which have no representation outside that country. Of several species grown worldwide, New Zealand also has a particularly large share. For example, it is estimated that New Zealand has some 30 species of Gigartina, a close relative of carrageen or Irish moss. These are often referred to as the New Zealand carrageens. The substance called agar which can be extracted from these species gives them great commercial application in the production of seameal, from which seameal custard (a food product) is made, and in the canning, paint and leather industries. Agar is also used in the manufacture of cough mixtures, cosmetics, confectionery and toothpastes. In fact, during World War II, New Zealand Gigartina were sent to Australia to be used in toothpaste.

C New Zealand has many of the commercially profitable red seaweeds, several species of which are a source of agar (Pterocladia, Gelidium, Chondrus, Gigartina). Despite this, these seaweeds were not much utilised until several decades ago. Although distribution of the Gigartina is confined to certain areas according to species, it is only on the east coast of the North Island that its occurrence is rare. And even then, the east coast, and the area around Hokianga, have a considerable supply of the two species of Pterocladia from which agar is also made. New Zealand used to import the Northern Hemisphere Irish moss (Chondrus crispus) from England and ready-made agar from Japan.

D Seaweeds are divided into three classes determined by colour – red, brown and green – and each tends to live in a specific position. However, except for the unmistakable sea lettuce (Ulva), few are totally one colour; and especially when dry, some species can change colour significantly – a brown one may turn quite black, or a red one appear black, brown, pink or purple. Identification is nevertheless facilitated by the fact that the factors which determine where a seaweed will grow are quite precise, and they tend therefore to occur in very well-defined zones. Although there are exceptions, the green seaweeds are mainly shallow-water algae; the browns belong to the medium depths; and the reds are plants of the deeper water, furthest from the shore. Those shallow-water species able to resist long periods of exposure to sun and air are usually found on the upper shore, while those less able to withstand such exposure occur nearer to, or below, the low-water mark. Radiation from the sun, the temperature level, and the length of time immersed also play a part in the zoning of seaweeds. Flat rock surfaces near mid-level tides are the most usual habitat of sea-bombs, Venus’ necklace, and most brown seaweeds. This is also the home of the purple laver or Maori karengo, which looks rather like a reddish-purple lettuce. Deep-water rocks on open coasts, exposed only at very low tide, are usually the site of bull-kelp, strapweeds and similar tough specimens. Kelp, or bladder kelp, has stems that rise to the surface from massive bases or ‘holdfasts’, the leafy branches and long ribbons of leaves surging with the swells beyond the line of shallow coastal breakers or covering vast areas of calmer coastal water.

E Propagation of seaweeds occurs by seed-like spores, or by fertilisation of egg cells. None have roots in the usual sense; few have leaves; and none have flowers, fruits or seeds. The plants absorb their nourishment through their leafy fronds when they are surrounded by water; the holdfast of seaweeds is purely an attaching organ, not an absorbing one.

F Some of the large seaweeds stay on the surface of the water by means of air- filled floats; others, such as bull-kelp, have large cells filled with air. Some which spend a good part of their time exposed to the air, often reduce dehydration either by having swollen stems that contain water, or they may (like Venus’ necklace) have swollen nodules, or they may have a distinctive shape like a sea-bomb. Others, like the sea cactus, are filled with a slimy fluid or have a coating of mucilage on the surface. In some of the larger kelps, this coating is not only to keep the plant moist, but also to protect it from the violent action of waves.

Questions 1-6

Reading Passage 1 has six paragraphs, A-F.

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below.

List of Headings

i The appearance and location of different seaweeds

ii The nutritional value of seaweeds

iii How seaweeds reproduce and grow

iv How to make agar from seaweeds

v The under-use of native seaweeds

vi Seaweed species at risk of extinction

vii Recipes for how to cook seaweeds

viii The range of seaweed products

ix Why seaweeds don’t sink or dry out

1 Paragraph A

2 Paragraph B

3 Paragraph C

4 Paragraph D

5 Paragraph E

6 Paragraph F

Questions 7-10

Complete the flow-chart below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Questions 11-13

Classify the following characteristics as belonging to

A brown seaweed

B green seaweed

C red seaweed

Write the correct letter, A, B or C, in boxes 11-13 on your answer sheet.

11 can survive the heat and dryness at the high-water mark

12 grow far out in the open sea

13 share their site with karengo seaweed

Two Wings And A Toolkit

Betty and her mate Abel are captive crows in the care of Alex Kacelnik, an expert in animal behaviour at Oxford University. They belong to a forest-dwelling species of bird (Corvus rnoneduloides) confined to two islands in the South Pacific. New Caledonian crows are tenacious predators, and the only birds that habitually use a wide selection of self-made tools to find food.

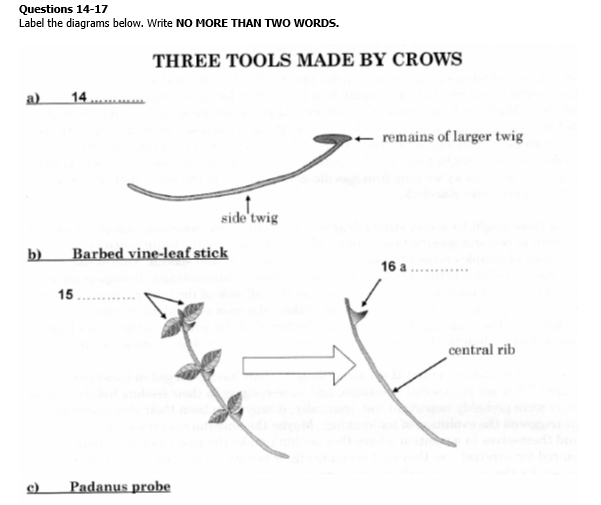

One of the wild crows’ cleverest tools is the crochet hook, made by detaching a side twig from a larger one, leaving enough of the larger twig to shape into a hook. Equally cunning is a tool crafted from the barbed vine-leaf, which consists of a central rib with paired leaflets each with a rose-like thorn at its base. They strip out a piece of this rib, removing the leaflets and all but one thorn at the top, which remains as a ready-made hook to prise out insects from awkward cracks.

The crows also make an ingenious tool called a padanus probe from padanus tree leaves. The tool has a broad base, sharp tip, a row of tiny hooks along one edge, and a tapered shape created by the crow nipping and tearing to form a progression of three or four steps along the other edge of the leaf. What makes this tool special is that they manufacture it to a standard design, as if following a set of instructions. Although it is rare to catch a crow in the act of clipping out a padanus probe, we do have ample proof of their workmanship: the discarded leaves from which the tools are cut. The remarkable thing that these ‘counterpart’ leaves tell us is that crows consistently produce the same design every time, with no in-between or trial versions. It’s left the researchers wondering whether, like people, they envisage the tool before they start and perform the actions they know are needed to make it. Research has revealed that genetics plays a part in the less sophisticated toolmaking skills of finches in the Galapagos islands. No one knows if that’s also the case for New Caledonian crows, but it’s highly unlikely that their toolmaking skills are hardwired into the brain. ‘The picture so far points to a combination of cultural transmission – from parent birds to their young – and individual resourcefulness,’ says Kacelnik.

In a test at Oxford, Kacelnik’s team offered Betty and Abel an original challenge – food in a bucket at the bottom of a ‘well’. The only way to get the food was to hook the bucket out by its handle. Given a choice of tools – a straight length of wire and one with a hooked end – the birds immediately picked the hook, showing that they did indeed understand the functional properties of the tool.

But do they also have the foresight and creativity to plan the construction of their tools? It appears they do. In one bucket-in-the-well test, Abel carried off the hook, leaving Betty with nothing but the straight wire. ‘What happened next was absolutely amazing,’ says Kacelnik. She wedged the tip of the wire into a crack in a plastic dish and pulled the other end to fashion her own hook. Wild crows don’t have access to pliable, bendable material that retains its shape, and Betty’s only similar experience was a brief encounter with some pipe cleaners a year earlier. In nine out of ten further tests, she again made hooks and retrieved the bucket.

The question of what’s going on in a crow’s mind will take time and a lot more experiments to answer, but there could be a lesson in it for understanding our own evolution. Maybe our ancestors, who suddenly began to create symmetrical tools with carefully worked edges some 1.5 million years ago, didn’t actually have the sophisticated mental abilities with which we credit them. Closer scrutiny of the brains of New Caledonian crows might provide a few pointers to the special attributes they would have needed. ‘If we’re lucky we may find specific developments in the brain that set these animals apart,’ says Kacelnik.

One of these might be a very strong degree of laterality – the specialisation of one side of the brain to perform specific tasks. In people, the left side of the brain controls the processing of complex sequential tasks, and also language and speech. One of the consequences of this is thought to be right-handedness. Interestingly, biologists have noticed that most padanus probes are cut from the left side of the leaf, meaning that the birds clip them with the right side of their beaks – the crow equivalent of right- handedness. The team thinks this reflects the fact that the left side of the crow’s brain is specialised to handle the sequential processing required to make complex tools.

Under what conditions might this extraordinary talent have emerged in these two species? They are both social creatures, and wide-ranging in their feeding habits. These factors were probably important but, ironically, it may have been their shortcomings that triggered the evolution of toolmaking. Maybe the ancestors of crows and humans found themselves in a position where they couldn’t make the physical adaptations required for survival – so they had to change their behaviour instead. The stage was then set for the evolution of those rare cognitive skills that produce sophisticated tools. New Caledonian crows may tell us what those crucial skills are.

Questions 14-17

Label the diagrams below. Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS.

Questions 18-23

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 18-23 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

18 There appears to be a fixed pattern for the padanus probe’s construction.

19 There is plenty of evidence to indicate how the crows manufacture the padanus probe.

20 Crows seem to practise a number of times before making a usable padanus probe.

21 The researchers suspect the crows have a mental image of the padanus probe before they create it.

22 Research into how the padanus probe is made has helped to explain the toolmaking skills of many other bird species.

23 The researchers believe the ability to make the padanus probe is passed down to the crows in their genes.

Questions 24-26

Choose THREE letters, A-G.

According to the information in the passage, which THREE of the following features are probably common to both New Caledonian crows and human beings?

A keeping the same mate for life

B having few natural predators

C having a bias to the right when working

D being able to process sequential tasks

E living in extended family groups

F eating a variety of foodstuffs

G being able to adapt to diverse habitats

How Did Writing Begin?

The Sumerians, an ancient people of the Middle East, had a story explaining the invention of writing more than 5,000 years ago. It seems a messenger of the King of Uruk arrived at the court of a distant ruler so exhausted that he was unable to deliver the oral message. So the king set down the words of his next messages on a clay tablet. A charming story, whose retelling at a recent symposium at the University of Pennsylvania amused scholars. They smiled at the absurdity of a letter which the recipient would not have been able to read. They also doubted that the earliest writing was a direct rendering of speech. Writing more likely began as a separate, symbolic system of communication and only later merged with spoken language.

Yet in the story the Sumerians, who lived in Mesopotamia, in what is now southern Iraq, seemed to understand writing’s transforming function. As Dr Holly Pittman, director of the University’s Center for Ancient Studies, observed, writing ‘arose out of the need to store and transmit information … over time and space’.

In exchanging interpretations and information, the scholars acknowledged that they still had no fully satisfying answers to the questions of how and why writing developed. Many favoured an explanation of writing’s origins in the visual arts, pictures becoming increasingly abstract and eventually representing spoken words. Their views clashed with a widely held theory among archaeologists that writing developed from the pieces of clay that Sumerian accountants used as tokens to keep track of goods.

Archaeologists generally concede that they have no definitive answer to the question of whether writing was invented only once, or arose independently in several places, such as Egypt, the Indus Valley, China, Mexico and Central America. The preponderance of archaeological data shows that the urbanizing Sumerians were the first to develop writing, in 3,200 or 3,300 BC. These are the dates for many clay tablets in an early form of cuneiform, a script written by pressing the end of a sharpened stick into wet clay, found at the site of the ancient city of Uruk. The baked clay tablets bore such images as pictorial symbols of the names of people, places and things connected with government and commerce. The Sumerian script gradually evolved from the pictorial to the abstract, but did not at first represent recorded spoken language.

Dr Peter Damerow, a specialist in Sumerian cuneiform at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, said, ‘It is likely that there were mutual influences of writing systems around the world. However, their great variety now shows that the development of writing, once initiated, attains a considerable degree of independence and flexibility to adapt to specific characteristics of the sounds of the language to be represented.’ Not that he accepts the conventional view that writing started as a representation of words by pictures. New studies of early Sumerian writing, he said, challenge this interpretation. The structures of this earliest writing did not, for example, match the structure of spoken language, dealing mainly in lists and categories rather than in sentences and narrative.

For at least two decades, Dr Denise Schmandt-Besserat, a University of Texas archaeologist, has argued that the first writing grew directly out of a system practised by Sumerian accountants. They used clay tokens, each one shaped to represent a jar of oil, a container of grain or a particular kind of livestock. These tokens were sealed inside clay spheres, and then the number and type of tokens inside was recorded on the outside using impressions resembling the tokens. Eventually, the token impressions were replaced with inscribed signs, and writing had been invented.

Though Dr Schmandt-Besserat has won much support, some linguists question her thesis, and others, like Dr Pittman, think it too narrow. They emphasise that pictorial representation and writing evolved together. ‘There’s no question that the token system is a forerunner of writing,’ Dr Pittman said, ‘but I have an argument with her evidence for a link between tokens and signs, and she doesn’t open up the process to include picture making.’

Dr Schmandt-Besserat vigorously defended her ideas. ‘My colleagues say that pictures were the beginning of writing/ she said, ‘but show me a single picture that becomes a sign in writing. They say that designs on pottery were the beginning of writing, but show me a single sign of writing you can trace back to a pot – it doesn’t exist.’ In its first 500 years, she asserted, cuneiform writing was used almost solely for recording economic information, and after that its uses multiplied and broadened.

Yet other scholars have advanced different ideas. Dr Piotr Michalowski, Professor of Near East Civilizations at the University of Michigan, said that the proto-writing of Sumerian Uruk was ‘so radically different as to be a complete break with the past’. It no doubt served, he said, to store and communicate information, but also became a new instrument of power. Some scholars noted that the origins of writing may not always have been in economics. In Egypt, most early writing is high on monuments or deep in tombs. In this case, said Dr Pascal Vernus from a university in Paris, early writing was less administrative than sacred. It seems that the only certainty in this field is that many questions remain to be answered.

Questions 27-30

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

27 The researchers at the symposium regarded the story of the King of Uruk as ridiculous because

A writing probably developed independently of speech

B clay tablets had not been invented at that time

C the distant ruler would have spoken another language

D evidence of writing has been discovered from an earlier period

28 According to the writer, the story of the King of Uruk

A is a probable explanation of the origins of writing

B proves that early writing had a different function to writing today

C provides an example of symbolic writing

D shows some awareness amongst Sumerians of the purpose of writing

29 There was disagreement among the researchers at the symposium about

A the area where writing began

B the nature of early writing materials

C the way writing began

D the meaning of certain abstract images

30 The opponents of the theory that writing developed from tokens believe that it

A grew out of accountancy

B evolved from pictures

C was initially intended as decoration

D was unlikely to have been connected with commerce

Questions 31-36

Look at the following statements (Questions 31-36) and the list of people below.

Match each statement with the correct person, A-E.

31 There is no proof that early writing is connected to decorated household objects.

32 As writing developed, it came to represent speech.

33 Sumerian writing developed into a means of political control.

34 Early writing did not represent the grammatical features of speech.

35 There is no convincing proof that tokens and signs are connected.

36 The uses of cuneiform writing were narrow at first, and later widened.

List of People

A Dr Holly Pittman

B Dr Peter Damerow

C Dr Denise Schmandt-Besserat

D Dr Piotr Michalowski

E Dr Pascal Vernus

Questions 37-40

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-N, below.

The earliest form of writing

Most archaeological evidence shows that the people of (37)……………………………invented writing in around 3,300 BC. Their script was written on (38)……………………………and was called (39)………………………………..Their script originally showed images related to political power and business, and later developed to become more (40)………………………….

| A cuneiform | B pictorial | C tomb walls | D urban | E legible |

| F stone blocks | G simple | H Mesopotamia | I abstract | J papyrus sheets |

| K decorative | L clay tablets | M Egypt | N Uruk |