The Grapes of Winter

A Icewine, or Eiswein as the Germans call it, is the product of frozen grapes. A small portion of the vineyard is left unpicked during the fall harvest’ those grapes are left on the vine until the mercury drops to at least -7°C. At this temperature, the sugar-rich juice begins to freeze. If the grapes are picked in their frozen state and pressed while they are as hard as marbles, the small amount of juice recovered is intensely sweet and high in acidity. The amber dessert wine made from this juice is an ambrosia fit for Dionysus himself – very sweet, it combines savours of peach and apricot.

B The discovery of icewine, like most epicurean breakthroughs was accidental. In 1794, wine producers in the German duchy of Franconia made virtue of necessity by pressing juice from frozen grapes. They were amazed by an abnormally high concentration of sugars and acids which until then had been achieved only by drying the grapes on straw mats before pressing or by the effects of Botrytis cinerea, a disease known as ‘root rot’. Botrytis cinerea afflicts grapes in autumn, usually in regions where there is early morning fog and humid, sunny afternoons. A mushroom-like fungus attaches itself to the berries, puncturing their skins and allowing the juice to evaporate. The world’s great dessert wines, such as Sauternes, Riesling and Tokay Aszy Essentia, are made from grapes afflicted by this benign disease.

C It was not until the mid- 19th century in the Rheingau region of northwestern Germany that winegrowers made conscious efforts to produce icewine on a regular basis. But they found they could not make it every year since the subzero cold spell must last several days to ensure that the berries remain frozen solid during picking and the pressing process, which alone can take up to three days or longer. Grapes are 80 percent water; when this water is frozen and driven off under pressure and shards of ice, the resulting juice is wonderfully sweet. If the ice melts during a sudden thaw, the sugar in each berry is diluted.

D To ensure the right temperature is maintained, in Germany the pickers must be out well before dawn to harvest the grapes. Not all grapes are suitable for icewine. Only the thick-skinned, late-maturing varieties such as Riesling and Vidal can resist such predators as grey rot, powdery mildew, unseasonable warmth, wind, rain and the variety of fauna craving a sweet meal. Leaving grapes on the vine once they have ripened is an enormous gamble. If birds and animals don’t get them, mildew and rot or a sudden storm might. So growers reserve only a small portion of their Vidal or Riesling grapes for icewine, a couple of hectares of views at most. A vineyard left for icewine is a sorry sight. The mesh-covered vines are denuded of leaves and the grapes are brown and shrivelled, dangling like tiny bats from the frozen canes. The stems of the grape clusters are dry and brittle. A strong wind or an ice storm could easily knock the fruit to the ground. A twist of the wrist is all that is needed to pick the grapes. But wine the wind howls through the vineyard, driving the snow before it and the wind chill factor can make a temperature of -10° seem like -40°, harvesting icewine grapes becomes a decidedly uncomfortable business. Pickers fortified with tea and brandy, brave the elements for two hours at a time before rushing back to the winery to warm up.

E Once the tractor delivers the precious boxes of grapes to the winery, the really hard work begins. Since the berries must remain frozen, the pressing is done either outdoors or inside the winery with the doors left open. The presses have to be worked slowly otherwise the bunches will turn to a solid block of ice yielding nothing. Some producers throw rice husks into the press to pierce the skins of the grapes and create channels for the juice to flow through the mass of ice. Sometimes it takes two or three hours before the first drop of juice appears.

F A kilogram of unfrozen grapes normally produces sufficient juice to ferment into one bottle of wine. The juice from a kilogram of icewine grapes produces one-fifth of that amount or less depending on the degree of dehydration caused by wind and winter sunshine. The longer the grapes hang on the vine, the less juice there is. So grapes harvested during a cold snap in December will yield more icewine than if they are picked in February. The oily juice, once extracted from the marble-hard berries, is allowed to settle for three or four days. It is then clarified of dust and debris by racking from one tank to another. A special yeast is added to activate fermentation in the stainless steel tanks since the colourless liquid is too cold to ferment on its own. Because of the high sugars, the fermentation is slow and can take months. But when the wine is finally bottled, it has the capacity to age for a decade or more.

G While Germany may be recognised as the home of icewine, its winemakers cannot produce it every year. Canadian winemakers can and are slowly becoming known for this expensive rarity as the home-grown product garners medals at international wine competitions. Klaus Reif of the Reif Winery at Niagara-on-the-Lake has produced icewine in both countries. While studying oenology, the science of winemaking, he worked at a government winery in Neustadt in the West German state of Rheinland-Pfalz. In 1983 he made his first Canadian icewine from Riesling grapes. Four years later he made ice-wine from Vidal grapes grown in his uncle’s vineyard at Niagara-on-the-Lake. “The juice comes out like honey here” says Reif, “in Germany it drops like ordinary wine”.

Questions 1-7

From the list of headings below, choose the most suitable heading for each paragraph.

List of Headings

i. Award-winning wine

ii. Temperature vital to production

iii. Early caution and challenge

iv. A delicious taste

v. Picking the grapes, the only easy step

vi. From grape to wine

vii. The juice flows quickly

viii. Disease brings benefits

ix. The role of climate in taste

x. Obstacles to production

1 Paragraph A

2 Paragraph B

3 Paragraph C

4 Paragraph D

5 Paragraph E

6 Paragraph F

7 Paragraph G

Questions 8-10

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

8 Growers set aside only a small area for icewine grapes because

A not all grapes are suitable

B nature attacks them in various ways

C not many grapes are needed

D the area set aside makes the vineyard look extremely untidy

9 Rice husks are used because they

A stop the grapes from becoming ice blocks

B help the berries to remain frozen

C create holes in the grapes

D help producers create different tastes

10 According to Klaus Reif, Canadian icewine

A flows more slowly than German wine

B tastes a lot like German icewine

C is better than German icewine

D is sweeter than German icewine

Questions 11-14

Complete each of the following statements (questions 11-14) with the best ending A-G from the box below.

11 Franconia icewine makers

12 Famous dessert winemakers

13 Icewine grape pickers in Germany

14 Canadian icewine makers

A use diseased grapes to produce their wine.

B enjoy working in cool climates.

C can produce icewine every year.

D were surprised by the high sugar content in frozen grapes.

E made a conscious effort to produce ice wine.

F drink tea and brandy during their work.

Islands That Float

Islands are not known for their mobility but, occasionally it occurs. Natural floating islands have been recorded in many parts of the world (Burns et al 1985). Longevity studies in lakes have been carried out by Hesser, and in rivers and the open sea by Boughey (Smithsonian Institute 1970). They can form in two common ways: landslides of (usually vegetated) peaty soils into lakes or seawater or as a flotation of peat soils (usually bound by roots of woody vegetation) after storm surges, river floods or lake level risings.

The capacity of the living part of a floating island to maintain its equilibrium in the face of destructive forces, such as fire, wave attack or hogging and sagging while riding sea or swell waves is a major obstacle. In general, ocean-going floating islands are most likely to be short-lived; wave wash-over gradually eliminates enough of the island’s store of fresh water to deplete soil air and kill vegetation around the edges which, in turn, causes erosion and diminishes buoyancy and horizontal mobility.

The forces acting on a floating island determine the speed and direction of movement and are very similar to those acting on floating mobile ice chunks during the partially open-water season (Peterson 1965). In contrast to such ice rafts, many floating islands carry vegetation, perhaps including trees which act as sails. Burns et al examined the forces acting and concluded that comparatively low wind velocities are required to mobilise free-floating islands with vegetation standing two meters or more tall.

The sighting of floating islands at sea is a rare event; such a thing is unscheduled, short-lived and usually undocumented. On July 4th, 1969, an island some 15 meters in diameter with 10-15 trees 10-12 meters tall was included in the daily notice to mariners as posing a shipping navigation hazard between Cuba and Haiti. McWhirter described the island as looking “…as though it were held together by a mangrove-type matting; there was some earth on it but it looked kind of bushy around the bottom, like there was dead foliage, grass-like material or something on the island itself. The trees were coming up out of that. It looked like the trees came right out of the surface brown layer. No roots were visible”. By the 14th of July the island had apparently broken up and the parts had partially submerged so that only the upper tree trunks were above the water. By July 19th, no trace of the island was found after an intensive six hour search.

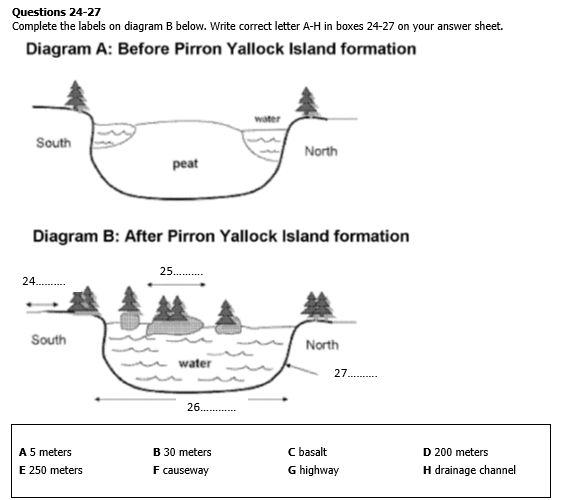

Another example albeit freshwater, can be found in Victoria, Australia – the floating islands of Pirron Yallock. Accounts of how the floating islands were formed have been given by local residents. These accounts have not been disputed in the scientific literature. Prior to 1938, the lake was an intermittent swamp which usually dried out in summer. A drainage channel had been excavated at the lowest point of the swamp at the northern part of its perimeter. This is likely to have encouraged the development or enlargement of a peat mat on the floor of the depression. Potatoes were grown in the centre of the depression where the peat rose to a slight mound. The peat was ignited by a fire in 1938 which burned from the dry edges towards a central damp section. A track was laid through the swamp last century and pavement work was carried out in 1929/30. This causeway restricted flow between the depression and its former southern arm. These roadworks, plus collapse and partial infilling of the northern drainage channel, created drainage conditions conducive to a transition from swamp to permanent lake.

The transformation from swamp to lake was dramatic, occurring over the winter of 1952 when rainfall of around 250mm was well above average. Peat is very buoyant and the central raised section which had been isolated by the fire, broke away from the rocky, basalt floor as the water level rose in winter. The main island then broke up into several smaller islands which drifted slowly for up to 200 meters within the confines of the lake and ranged in size from 2 to 30 meters in diameter. The years immediately following experienced average or above average rainfall and the water level was maintained. Re-alignment of the highway in 1963 completely blocked the former southern outlet of the depression, further enhancing its ability to retain water. The road surface also provided an additional source of runoff to the depression.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that the islands floated uninterrupted for 30 years following their formation. They generally moved between the NW and NE sides of the lake in response to the prevailing winds. In 1980, the Rural Water Commission issued a nearby motel a domestic licence to remove water from the lake and occasionally water is taken for the purpose of firefighting. The most significant amount taken for firefighting was during severe fires in February 1983. Since then, the Pirron Yallock islands have ceased to float, and this is thought to be related to a drop in the water level of approximately 600 mm over the past 10-15 years. The islands have either run aground on the bed or the lagoon or vegetation has attached them to the bed.

Floating islands have attracted attention because they are uncommon and their behaviour has provided not only explanations for events in myth and legend but also great scope for discussion and speculation amongst scientific and other observers.

Questions 15-19

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2?

In boxes 15-19 on your answer sheet write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

15 Natural floating islands occur mostly in lakes.

16 Floating Islands occur after a heavy storm or landslide.

17 The details of the floating island at sea near Cuba and Haiti were one of many sea-going islands in that area.

18 Floating islands at sea sink because the plants on them eventually die.

19 Scientists and local residents agree on how the Pirron Yallock Islands were formed.

Questions 20-23

Look at the following people (questions 20-23) and the list of statements below. Match each person to the correct statement. Write the correct letter A-G in boxes 1-4 on your answer sheet.

20 Burns

21 Peterson

22 McWhirter

23 Hesser

A compared floating islands to floating blocks of ice

B documented the break up of a sea-going island

C floating islands last longer when confined to a limited area

D studied the effect of rivers on floating islands

E like floating islands, floating mobile ice chunks carry vegetation

F even comparatively light winds can create a floating island

G recorded the appearance of a sea-going floating island

H tall trees increase floating island mobility

Ocean Plant life in decline

A Scientists have discovered plant life covering the surface of the world’s oceans is disappearing at a dangerous rate. This plant life called phytoplankton is a vital resource that helps absorb the worst of the ‘greenhouse gases’ involved in global warming. Satellites and ships at sea have confirmed the diminishing productivity of the microscopic plants, which oceanographers say is most striking in the waters of the North Pacific – ranging as far up as the high Arctic. “Whether the lost productivity of the phytoplankton is directly due to increased ocean temperatures that have been recorded for at least the past 20 years remains part of an extremely complex puzzle”, says Watson W. Gregg, a NASA biologist at the Goddard Space Flight Center in the USA, but it surely offers a fresh clue to the controversy over climate change. According to Gregg, the greatest loss of phytoplankton has occurred where ocean temperatures have risen most significantly between the early 1980s and the late 1990s. In the North Atlantic summertime, sea surface temperatures rose about 1.3 degrees Fahrenheit during that period, while in the North Pacific the ocean’s surface temperatures rose about .07 of a degree.

B While the link between ocean temperatures and the productivity of plankton is striking, other factors can also affect the health of the plants. They need iron as nourishment, for example, and much of it reaches them in powerful winds that sweep iron-containing dust across the oceans from continental deserts. When those winds diminish or fail, plankton can suffer. According to Gregg and his colleagues, there have been small but measurable decreases in the amount of iron deposited over the oceans in recent years.

C The significant decline in plankton productivity has a direct effect on the world’s carbon cycle. Normally, the ocean plants take up about half of all the carbon dioxide in the world’s environment because they use the carbon, along with sunlight, for growth, and release oxygen into the atmosphere in a process known as photosynthesis. Primary production of plankton in the North Pacific has decreased by more than 9 percent during the past 20 years, and by nearly 7 percent in the North Atlantic, Gregg and his colleagues determined from their satellite observations and shipboard surveys. Studies combining all the major ocean basins of the world, has revealed the decline in plankton productivity to be more than 6 percent.

D The plankton of the seas are a major way in which the extra carbon dioxide emitted in the combustion of fossil fuels is eliminated. Whether caused by currently rising global temperatures or not, the loss of natural plankton productivity in the oceans also means the loss of an important factor in removing much of the principal greenhouse gas that has caused the world’s climate to warm for the past century or more. “Our combined research shows that ocean primary productivity is declining, and it may be the result of climate changes such as increased temperatures and decreased iron deposits into parts of the oceans. This has major implications for the global carbon cycle” said Gregg.

E At the same time, Stanford University scientists using two other NASA satellites and one flown by the Defense Department have observed dramatic new changes in the vast ice sheets along the west coast of Antarctica. These changes, in turn, are having a major impact on phytoplankton there. They report that a monster chunk of the Ross Ice Shelf – an iceberg almost 20 miles wide and 124 miles long – has broken off the west face of the shelf and is burying a vast ocean area of phytoplankton that is the base of the food web in an area exceptionally rich in plant and animal marine life.

F Although sea surface temperatures around Western Antarctica are remaining stable, the loss of plankton is proving catastrophic to all the higher life forms that depend on the plant masses, say Stanford biological oceanographers Arrigo and van Dijken. Icebergs in Antarctica are designated by letters and numbers for aerial surveys across millions of square miles of the southern ocean, and this berg is known as C-19. “We estimate from satellite observations that C-19 in the Ross Sea has covered 90 percent of all the phytoplankton there” said Arrigo.

G Huge as it is, the C-19 iceberg is only the second-largest recorded in the Ross Sea region. An even larger one, dubbed B-15, broke off, or ‘calved’ in 2001. Although it also blotted out a large area of floating phytoplankton on the sea surface, it only wiped out about 40 percent of the microscopic plants. Approximately 25 percent of the world’s populations of emperor penguins and 30 percent of the Adelie penguins nest in colonies in this area. This amounts to hundreds of thousands of Adelie and emperor penguins all endangered by the huge iceberg, which has been stuck against the coast ever since it broke off from the Ross Ice Shelf last year. Whales, seals and the millions of shrimp-like sea creatures called krill are also threatened by the loss of many square miles of phytoplankton.

Questions 28-32

The passage has seven paragraphs labelled A-G. Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter A-G in boxes 28-32 on your answer sheet. NB: You may use any letter more than once.

28 the role of plankton in dealing with carbon dioxide from vehicles

29 the effect on land and marine creatures when icebergs break off

30 the impact of higher temperatures upon the ocean

31 the system used in naming icebergs

32 the importance of phytoplankton in the food chain

Questions 33-36

Complete the sentences below with words taken from Reading Passage 3. Use NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS for each answer.

33 Much needed iron for plant life is transported to the ocean by………………..

34 An increase in greenhouse gasses is due to a decrease in…………………..

35 Phytoplankton forms the………………………………of the food web.

36 The technical term used when a piece of ice detached from the main block is…………………..

Questions 37-40

Complete the summary of paragraphs A-C below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

A decline in the plant life located in the world’s oceans has been validated by (37)………………………………..The most obvious decline in plant life has been in the North Pacific. A rise in ocean temperatures in the early 1980s and late 1990s led to a decline in (38)………………………………… In addition to higher ocean temperatures, deficiencies in (39)………………………. can also lead to a decline in plankton numbers. This, in turn, impacts upon the world’s (40)……………